Lichess

Can I random walk myself to 2300?

Instead of relying on actual skill, I wondered whether random rating fluctuations are sufficient to push myself over the 2300 Fide barrier. Here follows a mathematical investigation.I am happy and proud to announce I have reached 2200 Fide rating and managed to maintain it for quite a while now. The reaching was pretty hard, the maintaining not so much, I just stopped playing chess. I would say I’m not particularly obsessed by fancy titles and such, but nevertheless, as every 2200 player secretly does, you start looking upwards. At 2300 Fide you are ‘granted’ the Fide Master (FM) title (well, actually you have to buy it, but the money requirement is less stringent than the rating requirement, I would say).

Having this title comes with many social advantages, at least within the chess community. You get some minor reductions on tournament fees, people in Lichess chat suddenly respect you and you can brag about it against the friends you would have had if you had not consistently beaten them at chess during high school. It’s the good life. Outside the chess world, things don’t change very much, by the way. You don’t get any tax reductions, people still treat you like crap, etc. Some of them might think an FM-title means you have a job as frequency modulator at the local radio station, though.

So, whilst carefully thinking about these prosperities, a horrible thought crossed my mind: “What if I’m not good enough at chess?”. How terrifying! Do I have to do training and study? I mean, come on, it’s 2025. I don’t want to use my brain. We live in a modern, technological society. There has to be a way to achieve our goals whilst absolutely minimizing any form of effort.

Then I figured: to reach 2300 once, you don’t actually need to have 2300-strength. It’s how rating works. You have a certain strength, and your displayed rating hovers around this value. Sometimes it’s a little lower, sometimes it’s a little higher. It fluctuates around the average, and even though it usually stays pretty close to the average, larger deviations can naturally occur from time to time. It’s some kind of statistical process. Against a perfectly equal opponent, you are expected to score 50%. But you might win! And perhaps you win again. And perhaps a third time. Every game you take a step either upwards (if win) or downwards (if lose). A mathematical concept called ‘random walk’ comes to mind. The equivalent term ‘drunkards walk’ might connect to the average chess players understanding too.

About random walks

There are multiple forms of random walks, but in its most elementary form, it’s just a point on the (1D) number line that continuously takes steps of size 1 randomly to either the left or the right. Now regretfully, this isn’t a very good strategy to get very far. Left and right both have 50% chance to be chosen each step (there is symmetry; there is no directional preference), so you’re expected to stay pretty close to your starting point. However, given a large amount of steps N, you might cover quite some distance by randomly having chosen one direction over another.

The rating system is similar. When playing an equally strong opponent, you have 50% chance to win and 50% chance to lose (and we pretend draws do not exist...). So your rating either goes up by, say, +8 points or it goes down by -8 points. But here comes the obvious difference compared to a true random walk. If you play this same opponent whilst being severely overrated, your actual chance of winning remains 50%, but the steps up- or downwards aren’t equal anymore. You get penalized more for losing than that you get rewarded for winning. It becomes something like -9 and +7. Hence, the rating system makes sure you gravitate towards your real rating, and the further you go away from it, the stronger the pull.

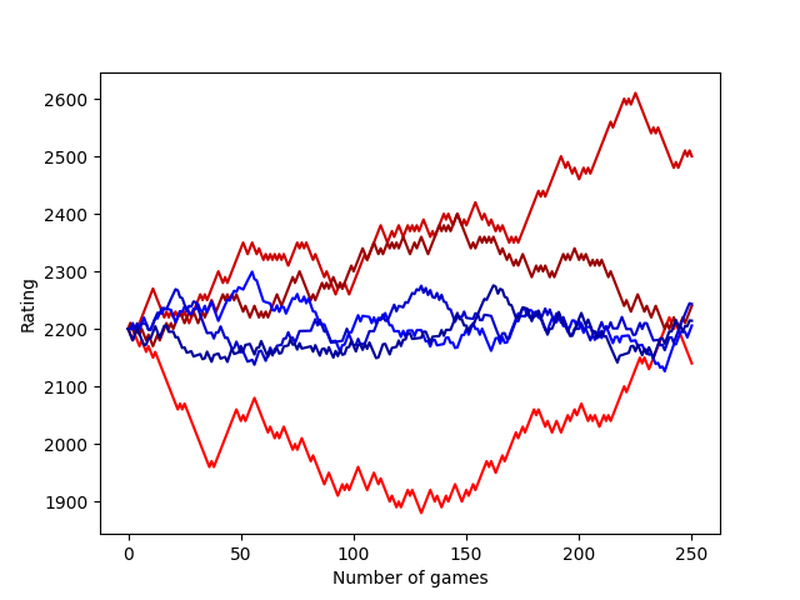

Here above is a plot created with a simple python script. The red lines are some examples of true random walks (with step size 8 to mimic chess) and the blue lines are simulations of chess games, where a 2200-rated player consistently plays against other 2200-rated players. So, as mentioned, true random walks have no real incentive to stay close to their starting value, so they tend to wander off in some random direction. Chess-random-walks fluctuate around the real rating of 2200.

And here’s the awesome news: sometimes the blue lines cross the magical 2300 barrier! So there is hope! Admittedly, it doesn't happen very often, so it might take a tremendous amount of games, but at least my plan is taking shape.

The mathematical meaning of rating (and hence life, as rating=life)

Now, I know the people on The Internet are without exception always very nice and supportive, but I still feel the urgent need to settle some minor details before continuing. Some people, mainly those that believe in free will and deterministic universes, might claim that the outcome of chess games is not purely a statistic process. And I can understand why people would foolishly believe such nonsense. You could argue that other effects also play a role. Things like skill, piececolor, opening preparation, opponent playstyle, nerves, age, time format, nourishment, good sleep in a not-so-noisy hotel room, amount of caffeine in the coffee, bribery, poisoning the opponent, daily horoscope, the national lottery results and whether there in football on the telly tonight. But I feel like I have no control over these things. Today, I want to focus solely on the mathematical characteristics. And yes, I cannot control random fluctuations either, as they are, well, by definition random. But hey, at least I can calculate the uncertainties then.

So, for the upcoming calculations, I’m just going to assume we have a chess player with a real strength R_real, and his displayed rating R hovers around this value. This poor guy has to play endless amount of games against an equally strong opponent, rated R_opp = R_real. (I performed simulations with all kinds of distributions of opponents with different R_opp, but the impacts were very insignificant, so I present only this simplified version here, with only a single opponent.)

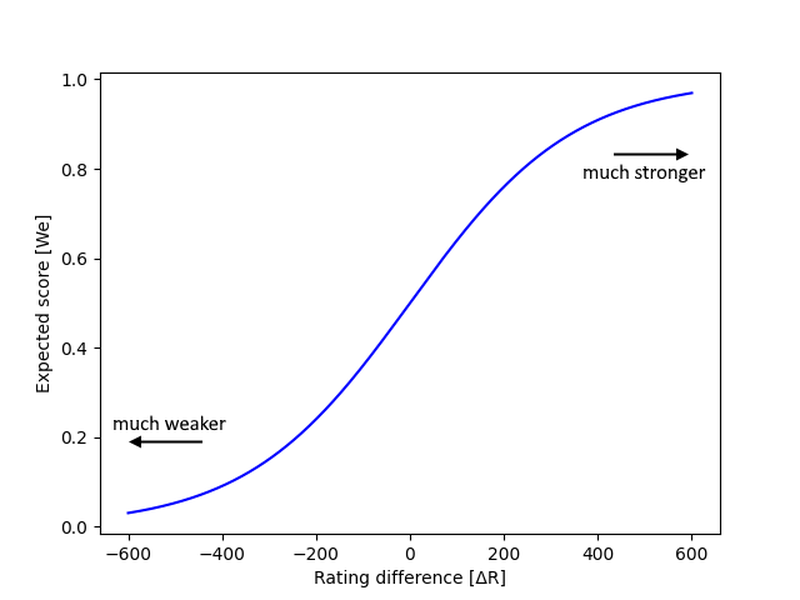

The good news with the rating system, is that everything is very well defined. The expected result, We, depends on the difference in rating, ΔR, between both players:

We = 0.5 + 0.5*tanh( 0.00288*ΔR )

I have rewritten the formula Wikipedia gives with the help of a hyperbolic tangent function. I think it’s more intuitive than the exponential form... So, if the players are equally strong, ΔR≈0, then you are expected to score around 0.5 points per game. If you are much stronger, ΔR=∞, then you are expected to win everything (1.0 points per game). And for ΔR=-∞, you will lose everything (0.0 points per game). No surprises here. Here's a graph:

However, there is this pretty annoying fundamental problem with this formula, that it doesn’t tell you how much of this expected score We consists of draws and how much of wins. This issue is a topic for a whole different post in itself, but for now I just assume we have 33.3% chance of winning, 33.3% chance of drawing and 33.3% chance of losing against our equal opponent, giving us We=0.5 on average, as it should.

The second ingredient we need for the analysis, is a formula for calculating how many points we get for a win, draw or loss. This is done by comparing the real result W (1.0, 0.5 or 0.0) with the expected result We, multiplied by some constant K, which Fide defines as K=20 for players of my strength:

New_rating = Old_rating + K * (W – We)

The central idea now, is that We depends on the displayed rating R in this case. If I get overrated, the value of We grows above 0.5. My real strength and my opponents strength stay the same, so W stays 0.5 on average. So on average, I will lose rating, until I’m no longer overrated.

How large are the rating fluctuations occurring naturally?

With this framework ready, we can calculate how much ratings are generally expected to fluctuate. By just simulating the blue curves in the first graph with something like 10.000.000 steps, I found that roughly 0.18% of ratings are above 2300. But instead of running the random-number-generator millions of times, I figured it’s cleaner to actually derive a result mathematically. I don’t want to bother my poor reader with massive amounts of maths here, but basically I computed the rating distribution R that, when playing against R_opp with strength R_real, would yield exactly the same distribution before and after the game.

It gave this graph. First and foremost, the area below the graph between R=2300 and R=∞ turns out to be 0.18%, so the result agrees with the other simulation and is thus probably correct. It means that indeed, a staggering 0.18% of 2300-players are actually imposters that are 100 points overrated! My desire is to become such an imposter too.

Then, I noticed the curve looked suspiciously much like a normal distribution. I haven’t managed to prove it, but I’m pretty sure it is. (There’s probably some deeper mathematical reason.) I found a standard deviation of σ=34.75, meaning that a fluctuation of like 69.50 points around your true strength is perfectly natural.

Lower values of K effectively decrease step size after each win/lose, make ratings more stable, hence the distribution would get narrower. Lichess uses roughly K=12 for stable users. However, draw-rates are lower in blitz/bullet games, effectively increasing average step size. When I used a draw-rate of 12.5%, I find a very similar result of σ=30.80. So even on Lichess, fluctuating within some 100-point-range is nothing to worry about. If you are suddenly 300 points below you common rating, you might be on tilt though... Just saying.

How many games do I need to play to cross 2300 by randomness?

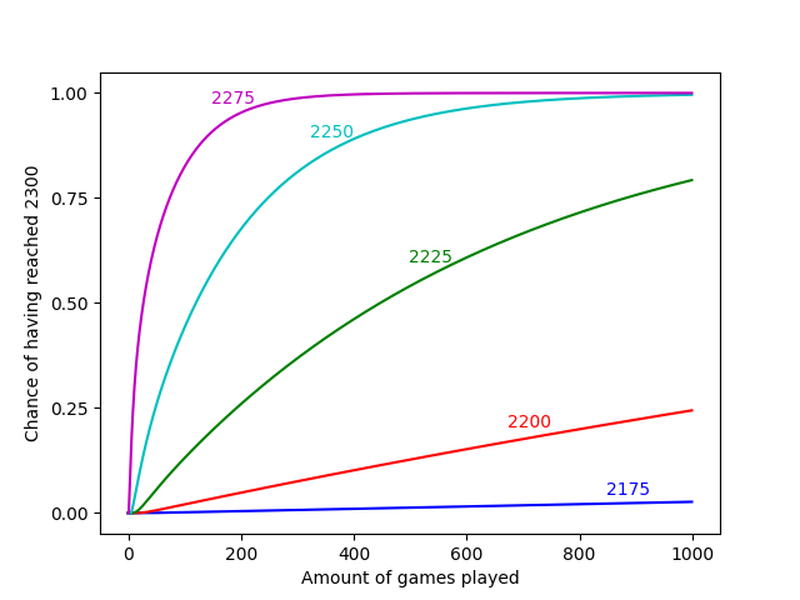

This is all fine and clever, but it doesn't actually tell me how many games I have to play before my random walk finally reaches 2300 for the first time. To calculate this, I used the following method: we start with a ‘group’ of random walkers at R=R_real, all 100% of them at the same spot. Then, all play a game. 33.3% win, 33.3% draw and 33.3% lose, splitting the group in three subgroups each with different rating R. The next round, these three groups split into nine groups. The next round 27 groups, then 81 groups. The total remains 100%, it’s just distributed into many subgroups. If a subgroup crosses the 2300-barrier however, we grant them the FM-title, and they are taken out of the game.

I like to think of it as drunkards doing random walks. When they reach 2300, they fall of a cliff, and we keep track of the dead bodies at the bottom of the ravine, piling up as time passes along.

Here’s the result. For R_real=2200, it actually takes quite some time. Only after 2432 games has 50% of the participants finally random walked itself over the finish line (it's so large, that it fell outside the graph). This is rather disappointing, to be fair... I hoped it would be less. I’m not really sure whether I have time to play thousands of classical games. It felt so fast when I just ran it through the computer.

But there’s hope. The amount of games needed decreases quickly with higher skill level. R_real=2275 only requires like 27 games. This makes sense. At this level, you only need like 2 or 3 games in a row going your way, and you’re done. But being 2250-level also works. You would need roughly 121 games then, which is a pretty feasible amount to play.

As mentioned before, there’s probably some way to calculate all the relations between all parameters exactly and derive formulas. But the math is not as straightforward as I initially thought, so I had to rely on a numerical approach here.

Conclusion

There are a couple of things to notice. First of all, I have hereby mathematically proved that the best way to reach a higher rating, is by getting better at chess. It’s very shocking. However, using random fluctuations works too. If you’re a very active player, having 2250 strength should be sufficient to become FM. If you’re not that active, 2275 will do.

But then a next question arises: how does one know his real strength? How can we be sure that our current ratings aren’t just a result of a series of positive coincidences? Am I an imposter right now? Randomness has a tendency to cause existential crises, and this blog is no exception.

Then, with these type of analyses, there is always a chance that other people already performed identical calculations, but just better. I guess there must have been professionals at Fide hired specifically to investigate the current rating system. But having said that, my one-minute search online wasn’t very fruitful. Wikipedia doesn’t go that deep, and the rest of the internet seems to be mainly worrying about the rating of random-mover-bots. So I dunno. I guess it’s not common knowledge at least.

But to conclude, this all sounds like a great plan to me. Improve a little, and then just wait until random rolls of the dice bring me to the desired level. You know, after reaching like 2225, I might just send Fide an email requesting my well-deserved title with this blog-post as attachment, arguing that I’m basically strong enough already, and that I just cannot be bothered by the trivial struggle of plowing through hundreds of games.

You may also like

DaBassie

DaBassieA radical opening experiment: The results

A few months ago I decided to only start playing openings unfamiliar to me. Now, after a boatload of… FM MathiCasa

FM MathiCasaChess Football: A Fun and Creative Variant

Where chess pieces become "players" and the traditional chessboard turns into a soccer field ChessMonitor_Stats

ChessMonitor_StatsWhere do Grandmasters play Chess? - Lichess vs. Chess.com

This is the first large-scale analysis of Grandmaster activity across Chess.com and Lichess from 200… DaBassie

DaBassieA mildly funny observation in the King’s Indian

Something about Be2 and Bd3. Admittedly, this is probably not the funniest thing you have ever read … CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… DaBassie

DaBassie